This article is part of the series "A Closer Look at Pass the Hash". Check out the rest:

Last week, I attended a webinar that was intended to give IT attendees a snapshot of recent threats—a kind of hacker heads-up. For their representative case, the two sec gurus described a clever and very targeted phishing attack. It led to an APT being secretly deposited in a DLL. Once the hackers were in, I was a little surprised to see they were probing memory for password hashes.

Pass the Hash, or PtH, I learned, was a standard hacker trick for gaining new identities. It makes sense. Hackers prefer to use credentials taken this way and logon directly as an existing user. Without sophisticated monitoring in place, they’re less likely to be spotted in real-time or even forensically afterwards when appearing as ordinary insiders.

Beware of Local Admin

As I mentioned last time, PtH assumes that an attacker has admin-level privileges on the machine they’ve first entered. The hash, which is kept in the memory space of a process with local admin permissions, is by itself not used to establish identity. Instead, it becomes part of a secret key for encrypting and decrypting messages in a challenge-response protocol.

In effect, you need just the hash code to take over the identity of another user. The hard part is getting local admin access.

Unfortunately, this is not a major hurdle. On older Windows systems (pre-Vista), the local admin account is automatically created and even worse, IT may have given each user machine the same admin password.

Suppose a laptop is compromised through a phish-mail that deposits malware. The malware succeeds in a brute force assault on the local admin passwords. From this machine, the hackers can leapfrog to other devices and servers, either through new credentials that’ve been scooped from memory by PtH toolkits or by simply reusing the admin password.

Thankfully, newer Windows OSes—Windows 7 and 8—by default don’t create a local admin account. Even better, Microsoft added a new malware defense known as User Account Controls or UAC, which requires explicit authorization for a user (or software) to gain elevated privileges.

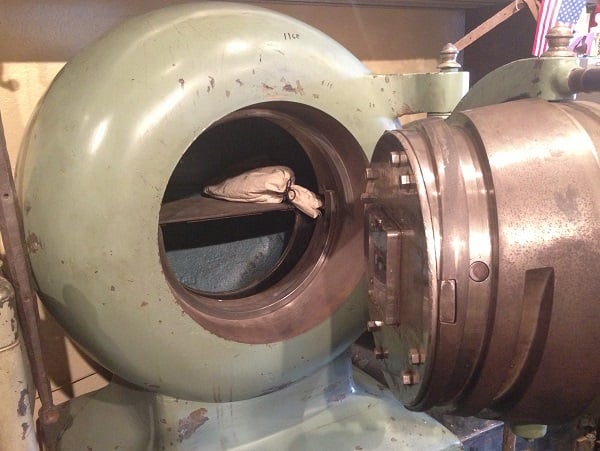

Admins know UAC through the Consent or Credential prompts (see pic) that pop up when they do legitimate work. While they may find this somewhat inconvenient, it does go a long way towards preventing malware and APTs from getting a critical foot hold.

For organizations with older OSes, IT can enforce a policy of creating unique and robust admin passwords for each user machine. It’s a low-effort remedy for preventing the hackers from easily guessing admin credentials and then reusing hashes on other machines. One simple trick is to append the machine name (or variation of it) to the password.

Stomp Out Local Network Logon Access

Another powerful mitigation that works on both old and new Windows OSes is to prevent ordinary and local admin users from directly networking into other users’ machines. In an Active Directory environment, you’d do that by using the Group Policy Object (GPO) Editor to disable Remote Desktop Connections. You can read more about how to do this here.

Quick summary: disable network and remote interactive logon privileges and then link users and groups to these specific User Rights policies.

And Just Limit Hashes

The above measures take care of a large part but not all the entry points for PtH attacks. In the exploit that I opened this post up with the hackers used SQL injection techniques to hijack a database server that was already running with elevated privileges. Result: they were able to scoop up high-level hashes.

The least privilege security principle now comes to the fore: don’t run services—SQL servers, and other IT infrastructure—with domain or enterprise level access rights. These permissions are far broader than what system tools and services generally need to do the job, and if the software is ever compromised, the shells or commands that are spawned automatically run at elevated access.

However, sometimes this may not be feasible, and of course, there are always zero-day exploits waiting to happen. So the key idea now is to limit the “bad” hashes—typically domain administrators—from spreading throughout the network. Recall that with Single Sign On, the hash, even for DAs, is always deposited in memory when logging onto a machine.

The rule is simple: only give domain administrators the right to access machines with equally high privilege levels—i.e., domain controllers—and never allow the same accounts access to plain-old employee laptops and desktops. You can always create a separate account for system admins for servicing user devices but with non-domain admin privileges.

That way, if a hacker (or internal user) should ever get control of a machine, they’ll never get the “keys to the kingdom”—a domain administrator’s hash that just happens to be in memory at the time.

What should I do now?

Below are three ways you can continue your journey to reduce data risk at your company:

Schedule a demo with us to see Varonis in action. We'll personalize the session to your org's data security needs and answer any questions.

See a sample of our Data Risk Assessment and learn the risks that could be lingering in your environment. Varonis' DRA is completely free and offers a clear path to automated remediation.

Follow us on LinkedIn, YouTube, and X (Twitter) for bite-sized insights on all things data security, including DSPM, threat detection, AI security, and more.